The oceans are sending us a distress signal, written in the bleached skeletons of coral reefs. As marine heatwaves intensify due to climate change, the intricate symbiotic relationship between corals and their algal partners is breaking down at an unprecedented rate. Scientists are now racing against time to develop innovative solutions, with coral-algal symbiont transplantation emerging as one of the most promising frontiers in reef restoration.

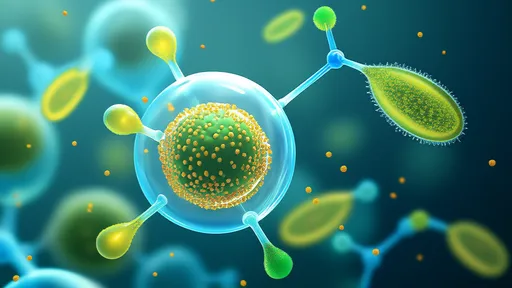

Beneath the waves, a microscopic drama determines the fate of entire ecosystems. Corals rely on photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae that live within their tissues, providing up to 90% of their energy needs through sugar production. When water temperatures rise just 1-2°C above normal, this delicate partnership shatters. The stressed algae either abandon their coral hosts or are violently expelled, leaving behind ghostly white skeletons in a process called coral bleaching.

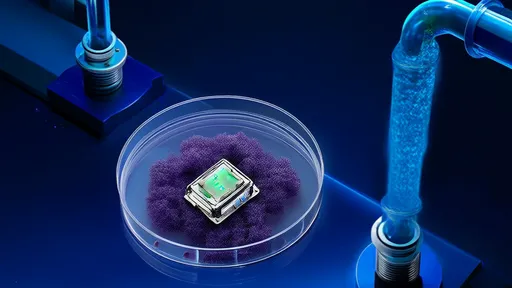

The traditional approach to reef restoration has focused on physically transplanting coral fragments to degraded areas. However, researchers are now looking deeper - literally at the cellular level - to address the root cause of bleaching. "We're not just moving corals anymore, we're engineering their very relationships," explains Dr. Elena Martinez, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Her team has been pioneering methods to introduce heat-resistant algal symbionts into vulnerable coral populations.

This cutting-edge work builds on a crucial discovery: not all zooxanthellae are created equal. Some algal strains, particularly those in the genus Durusdinium, can tolerate temperatures 3-4°C higher than their more common counterparts. These "super algae" naturally occur in small quantities but are now being cultivated and selectively introduced to boost coral resilience. The process involves extracting coral gametes or larvae and exposing them to these hardy symbionts during their most receptive developmental stages.

The results from early trials have been cautiously optimistic. In the Great Barrier Reef, corals inoculated with heat-tolerant algae showed 30-50% higher survival rates during moderate bleaching events compared to control groups. Perhaps more remarkably, these benefits appear to transfer to subsequent generations. "The algae don't just help the original coral survive - they become part of its biological legacy," notes Dr. Rajiv Singh, whose team at the Australian Institute of Marine Science has documented multi-generational heat resistance in treated corals.

However, the solution isn't as simple as mass-producing one type of super algae. Coral reefs are incredibly biodiverse, with different coral species often requiring specialized algal partners. Researchers at the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology have identified over a dozen thermally tolerant symbiont varieties, each suited to particular coral hosts. "It's like matching organ donors," says research coordinator Kaimana Lee. "We need to preserve the natural diversity while enhancing resilience."

The scale of implementation presents another challenge. Current methods remain labor-intensive, requiring teams of divers to carefully inoculate individual corals. Automated solutions are being tested, including biodegradable "algae capsules" that can be dispersed across reefs and release their contents when conditions are optimal. Meanwhile, cryopreservation techniques are being refined to create global libraries of algal strains, safeguarding genetic diversity for future restoration efforts.

Critics argue that such interventions distract from addressing the root cause of climate change. While most scientists agree that reducing carbon emissions remains paramount, many view symbiont transplantation as a critical stopgap measure. "Reefs can't wait for perfect policy solutions," argues Dr. Martinez. "We're buying time for corals to adapt while working on broader climate action."

The ethical dimensions are equally complex. Introducing non-native algal strains could potentially disrupt local ecosystems, and there are concerns about creating monocultures vulnerable to new threats. Regulatory frameworks are struggling to keep pace with the technology, leading to calls for international guidelines on assisted evolution techniques. The Coral Restoration Consortium recently established a working group specifically to address these biosafety concerns.

On the frontlines, reef managers are cautiously integrating these new tools. In the Florida Keys, a pilot project combines traditional coral gardening with selective symbiont enhancement. "We're seeing faster growth rates and better survival, especially in our staghorn coral outplants," reports marine specialist Carlos Mireles. Similar initiatives are underway in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and the Red Sea, each adapting the technology to local conditions.

The financial equation is shifting as well. While the initial costs of symbiont transplantation are higher than conventional methods, the potential long-term benefits could make it more economical. A recent economic analysis projected that reefs with enhanced thermal resistance could reduce restoration costs by up to 40% over a decade by minimizing repeat interventions after bleaching events.

Looking ahead, researchers are exploring even more advanced genetic approaches. Some labs are experimenting with directed evolution of algal strains, while others are investigating whether corals can be trained to better tolerate stress through epigenetic changes. The field is moving so rapidly that last year's breakthrough often becomes this year's standard practice.

For all the scientific progress, the ultimate test comes when summer temperatures peak. During the 2023 marine heatwave, several experimental plots with enhanced corals demonstrated remarkable resilience while surrounding reefs bleached severely. These real-world validations are giving hope to conservationists who have watched decades of reef decline. As Dr. Singh puts it: "We're not just documenting the death of reefs anymore - we're actively rewriting their survival story."

The coming decade will determine whether symbiont transplantation can scale from promising experiments to meaningful ecological impact. With coral reefs supporting 25% of marine species and providing coastal protection for millions of people, the stakes couldn't be higher. As the technology matures, its success may depend as much on social and political factors as on scientific ones - requiring unprecedented collaboration between researchers, governments, and local communities.

One thing is certain: the vision of scientists as passive observers of nature has forever changed. In the face of climate-driven catastrophe, marine biologists are becoming ecosystem engineers, carefully curating the microscopic partnerships that sustain our planet's most biodiverse marine habitats. The story of coral-algal symbiont transplantation isn't just about saving reefs - it's about redefining humanity's relationship with the natural world in the Anthropocene.

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025