For decades, the idea that trauma could be inherited seemed like science fiction. Yet emerging research in epigenetics has gradually shifted this notion from the realm of speculation into the arena of serious scientific inquiry. The latest breakthrough comes from a provocative hypothesis: memory RNA may serve as a molecular carrier of inherited trauma. This discovery, if substantiated, could rewrite our understanding of how experiences—especially painful ones—echo across generations.

The concept of trauma inheritance isn’t entirely new. Studies on Holocaust survivors and their descendants, as well as populations exposed to famine or extreme stress, have hinted at transgenerational effects. But the mechanism remained elusive. Traditional genetics couldn’t fully explain how environmental experiences left molecular scars on DNA, let alone how those scars persisted in offspring who never directly experienced the trauma. Enter memory RNA, a once-overlooked player now taking center stage.

Memory RNA: The Messenger of Experience

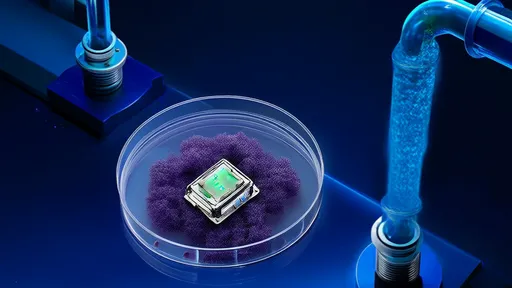

Unlike DNA, which is often seen as the static blueprint of life, RNA is dynamic and responsive. Certain types of RNA, particularly small non-coding RNAs, have been implicated in gene regulation and cellular memory. Recent experiments with model organisms—notably nematodes and mice—have shown that RNA extracted from traumatized individuals can induce similar behavioral or physiological changes in untreated subjects. This suggests that RNA doesn’t just carry genetic instructions; it might also encode experiential information.

In one groundbreaking study, researchers trained mice to associate a specific scent with fear. When RNA from these mice was injected into untrained subjects, the recipients exhibited heightened sensitivity to the same scent, despite never having encountered it before. The implications are staggering: a molecule, not just a gene, could transmit learned fear. If RNA can carry such specific "memories," it’s plausible that it also ferries the biochemical imprint of trauma across generations.

The Epigenetic Bridge

Memory RNA doesn’t act alone. It intersects with the broader epigenetic landscape—chemical modifications to DNA and histones that alter gene expression without changing the underlying genetic code. Trauma-induced changes in RNA profiles could potentially reshape epigenetic markers in germ cells (sperm and eggs), creating a conduit for heritable trauma. This two-hit model—RNA as the message, epigenetics as the medium—offers a compelling framework for how lived experiences become biological legacies.

Critics argue that the leap from worms and mice to humans is vast, and rightly so. Human trauma is complex, entangled with culture, psychology, and social context. Yet preliminary evidence is tantalizing. Analyses of blood samples from children of trauma survivors reveal altered RNA expression patterns linked to stress response pathways. These findings don’t prove causation, but they align with the hypothesis that RNA carries traces of ancestral adversity.

Ethical and Therapeutic Horizons

If memory RNA does underpin trauma inheritance, the ramifications extend far beyond academia. Ethically, it forces a reckoning with intergenerational accountability: how societies might address historical injustices that linger not just in collective memory but in biology. Therapeutically, it opens avenues for targeted interventions. Could neutralizing specific RNAs or reversing their epigenetic effects "erase" inherited trauma? Early-stage research on RNA-based therapies for PTSD hints at this possibility, though clinical applications remain distant.

The memory RNA hypothesis also challenges reductionist views of mental illness. Depression or anxiety in a descendant of trauma survivors might stem not only from upbringing or genetics but from literal molecular echoes of the past. This perspective could reduce stigma, framing certain disorders as physiological rather than purely psychological.

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

For all its promise, the memory RNA hypothesis raises as many questions as it answers. How exactly does experience become encoded in RNA? What prevents the system from being overwhelmed by "noise" from mundane daily stressors? And crucially, can these effects persist indefinitely, or do they fade over generations? Researchers are now developing tools to track RNA molecules across generations in real time, hoping to capture this elusive process in action.

Another frontier is the role of extracellular vesicles—tiny sacs that shuttle RNA between cells. These vesicles, found in bodily fluids like blood and semen, might facilitate RNA’s journey from somatic cells to germlines, ensuring trauma’s molecular signature isn’t lost between generations. Understanding this transport system could be key to manipulating it.

The memory RNA hypothesis is still young, and skepticism is healthy. Yet its potential to explain the invisible chains linking past and present is too profound to ignore. As research advances, we may find that our bodies are not just vessels for genes but living archives, carrying within us the whispers of ancestors we never knew.

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025